The Cabin Paradox

- Ema Drabik

- 5 days ago

- 9 min read

Simple Living, Growing Footprint

In recent years, interest in rural living has grown dramatically. Factors such as urban density, rising housing costs, and increasing expenses for utilities and food have contributed to this shift. For many, the appeal lies in having a quiet retreat for weekends or holidays, as well as the opportunity to reconnect with nature. In Scandinavia, however, this relationship with the countryside is not a new development; it has long been a cultural tradition, reflected in the widespread practice of maintaining family cabins. Norway, in particular, hosts a staggering 450 thousand cabins (this translates to about 12 people per cabin). As you travel the country, these cabins emerge in every setting: small huts hidden in valleys, generous family retreats on the edges of fjörds, and the expansive communal lodges of the DNT under massive mountains.

DNT cabins are a type of mountain or forest accomodation run by the Norwegian Trekking Association (DNT). There are three different kinds of DNT cabins, as defined by the official website (dnt.no):

Staffed lodges, Self-service cabins and No-service cabins.

Driving through Norway, one might notice how empty the landscape can feel. With a relatively small population of about 5.6 million (“Norway - Data Commons” 2024) concentrated mainly in Oslo and Bergen, much of the country’s vast land remains open. This abundance of space has allowed cabins to become a common feature across the countryside. Rooted in a tradition of retreat and simplicity, cabin culture emphasises stepping away from technology and everyday demands. As a result, for much of the year, many of these cabins remain unoccupied, waiting for weekends or holidays to be used.

Norway | Sweden | Finland | |

Population | 5.572 million1 | 10.57 million1 | 5.637 million1 |

Number of cabins | cca. 445,0002 | 628,1543 | cca. 503,7504 |

People per cabin (ppc) | 12 ppc | 17 ppc | 11 ppc |

Land area | 305,420 km2 5 | 407,280 km2 6 | 304,000 km2 7 |

1 World Bank. 2025. World Development Indicators.

2 Oyier, Boyd. 2020.

3 Statista. 2025. "Number of Privately Owned Holiday Houses in Sweden."

4 Statista. 2025. "Number of Holiday Houses in Finland by Region."

5 CountryReports.org. 2025. "Norway Use of Natural Resources.”

6 World Bank. 2025. "Land Area (sq. km) - Sweden."

7 Statistics Finland. 2025.

When Does a Tradition Really Begin?

The cabin, as we know it today, is largely a product of the post-Second World War era. Before the war, owning a cabin in a remote area was a privilege reserved for the elite. Today, that luxury has become far more widespread, with around half of Norway’s population claiming to own or have access to a cabin. Prior to the introduction of the Planning and Building Act in 1985, which, among other things, required municipalities to create land-use plans, cabins were built almost anywhere (MacHattie 2006). With no regulations in place beyond land ownership, clusters of cabins sprang up along scenic fjords and coastlines. To prevent the privatisation of coasts and beaches in popular scenic areas, the Planning and Building Act (PBA) was introduced, giving municipalities the authority to designate a set number of cabin plots and determine their locations. However, the measure came too late. When discussions of the PBA began in the 1970s, landowners rushed to build cabins before the legislation took effect. This led to a dramatic spike in low-quality construction, and by the time the PBA was enforced, most desirable plots had already been taken (Kinck, Hans E. 2023).

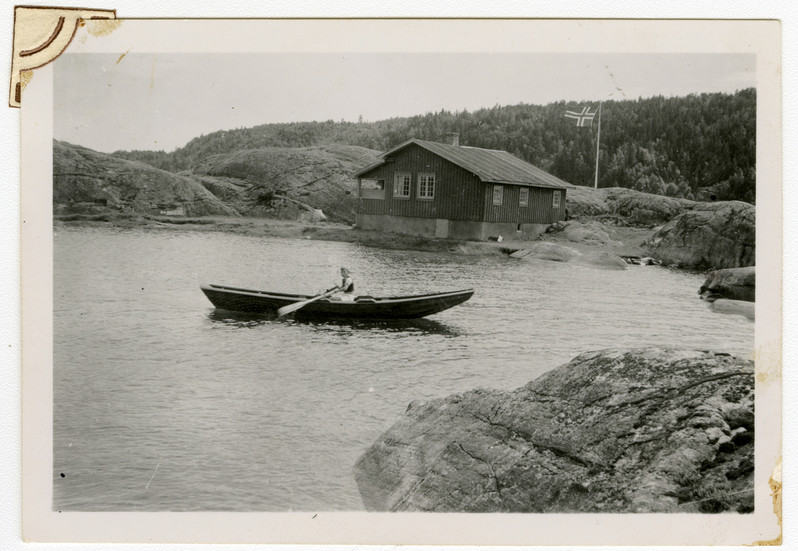

All photographs courtesy of the Oslo Museum digital archive

Cabins constructed during the 1950s through the 1970s reflected the values of traditional hytteliv. They were typically small, built from simple, local materials, and lacked electricity, running water, or indoor toilets. These modest structures functioned as basic shelters and embodied the idea of escape from everyday routines. It was not until later in the 20th century that more modern amenities became common. The first upgrades usually included electricity and running water, while toilets connected to sewage systems remained more difficult to implement (ScienceNorway 2023). For those unwilling to rely on an outhouse, many cabin owners today opt for a “Cinderella toilet,” an incineration toilet that has become a popular compromise (r/Norway 2022). With these upgrades, people started building larger cabins, adding guest rooms and larger amenities - where, initially, cabins usually only had one, maybe two rooms. By the 1990s, cabin size grew to about 66m2, in comparison to the traditional 50 - 60 m2. By the early 2000s, cabins often reached 90 m², and by 2018, the average size was around 96 m², with many falling in the 80–100 m² range (ScienceNorway 2023; Tandfonline 2020).

Hyttelivet: a term for “cabin life” in Norwegian.

Friluftsliv: a term for “life out in the open air, time spent in nature”, in Norwegian

A Shifting Culture.

Cabins have not only increased in size over the years, but their architectural expression is also shifting. In recent years, there has been debate about whether cabins built in rural clusters should follow the traditional design language, pitched roofs, local timber, and often the classic red facade, or whether they should “blend in” with the landscape in a more modern style. While most favour preserving the traditional look, many cabin owners have pushed back against this expectation, sparking heated discussions and even legal disputes.

This excerpt from “The Normal Cabin’s Revenge” by Simone Abram highlights a case where cabin owners found themselves in direct conflict with the law:

“In 2005, architect Henriette Salvesen and her husband Christopher Adams built a cabin in the popular mountain area of Hemsedal, yet tested the boundaries of the acceptable with their design of a modernist cabin with a flat roof. They entered into a prolonged legal battle with the planning authority, who eventually won its case that flat roofs went against the local planning directives in the area. Salvesen argued that the new plan and building law states that new buildings should be developed in contemporary styles that fit in the surroundings and that cabin areas deserved modern architecture. The levelling of plots with dynamite and the building of roads into new terrains, she argued, was a “rape of nature,” in stark contrast to her own cabin’s subtle emplacement in the landscape. A local Christian Democrat politician told the press that “there are sloping roofs on everything up here; it’s tradition, and it covers the whole of the district, that there should be sloping roofs” (with the notable exception of the 1960s town hall). Salvesen intended a flat turf roof, but despite calling on another mountain tradition it was not enough to satisfy the local planning committee. Further, it inspired a debate over modern architecture in cabins that rolled on through Architecture News. Failing in her attempt to overturn the ruling, Salvesen had a roof frame fitted to the building, but in making this roof effectively temporary (having no structural significance) was partly able to resist the ruling.”

(Abram 2012)

This growing interest in more modern and luxurious cabins reflects a broader shift in Norwegian hytteliv. For many with higher disposable incomes, rural cabins are no longer just simple shelters meeting basic needs. Instead, many newly built cabins function as fully equipped second homes, places where one can comfortably stay, without any connection to their primary dwelling. Several factors have contributed to this development: the rise of remote and flexible work opportunities, the steady increase in car ownership, and a general demand for greater comfort and convenience (Abram 2012; Xue 2020).

The Traditional Cabin

The traditional remote cabin usually consists of just one or two rooms. The kitchen’s most advanced feature is a wood-burning stove, typically made of cast iron or steel, while the rest of the space contains only simple cabinets and work surfaces - no sink. The living and sleeping areas, often combined into a single room, are located adjacent to the kitchen and are not always fully separated by walls. Candles, gas burners, and firewood are essential, serving as the cabin’s only sources of light and heat. This type of cabin represents the original form of hytteliv and remains a lingering example of its traditional roots.

An example of a well-preserved traditional cabin (Photographs courtesy of Finn.no, listing 413171685):

The cabin's sources of light aren't electrical - the hanging light in the living room is only a candle holder, and what appears to be a lamp hanging from the ceiling is a gas lamp with a lamp shade attached to it.

The kitchen's amenities are also very simple; no sink or running water and a gas stove.

author's note: Interestingly, while researching off-the-grid cabins, I relied primarily on finn.no, which offered a comprehensive view of the types of cabins currently on the Norwegian market. Without applying any filters, the first cabin lacking both running water and connected electricity appeared finally on the ninth page of my search. The most popular and sought-after cabins almost always had at least one of these amenities, with the majority offering both, and often more.

The filters were revealing as well. As expected, a button for selecting “Utedo-hytte”, a cabin with an outdoor/outhouse toilet and no plumbing, is non-existent. The only way to see a significant number of off-the-grid options was to limit cabin size to under 60 m². Even then, at least 30% of the results were in poor condition, neglected, or “demolition-ready.”

- 23 September 2025Timber Framing Techniques

The construction of a traditional hytte is grounded in the use of locally sourced timber, yet it allows for a variety of building techniques. Log construction, plank cladding, sod-roofed hybrids, and raised stone foundations are just a few of the combinations that can be employed, each responding to regional conditions, climate, and functional needs.

Type | Wall Construction | Roof Type | Flooring / Foundation | Materials | Notes / Regions |

Log Cabin (Laftet) | Stacked logs with corner notching (saddle or dovetail), structural load-bearing walls | Pitched roof; wooden shingles or turf | Timber floor on log or stone foundation | Pine or spruce logs | The most traditional form: widespread across forested regions, excellent thermal mass. |

Plank / Board Cabin (Kledning) | Timber frame with horizontal or vertical board cladding | Moderately pitched roof; wooden shingles | Timber floor on stone or concrete foundation (post-WWII) | Local timber, often painted | Became common with sawmill industrialisation, larger openings and more standardised layouts. |

Sod-Roof Cabin (Torvtak / Grøntak) | Log or plank walls | Turf roof layered over birch bark | Timber floor on log or stone foundation | Timber, birch bark, turf | Historic in western and northern Norway, strong insulation, often paired with lafting. |

Raised / Stone-Foundation Cabin | Log or plank walls | Pitched roof | Floor raised on stone piers or continuous stone base | Timber superstructure over stone | Protects from moisture and snow; common in humid or mountainous regions. Can combine with any wall type. |

The Paradox

The traditional formulation of “the cabin paradox” in Norway questioned why individuals invested heavily in improving their everyday comfort only to spend holidays in basic, remote cabins. This formulation is outdated. Modernisation has reached recreational cabins, reshaping their environmental footprint and cultural significance.

Norway's cabin modernisation is not inherently problematic. The country’s environmental policies, renewable energy systems, and low-carbon infrastructure continue to position it as a global leader in sustainability. The issue lies in the cumulative impact of expanding and upgrading recreational properties - an impact that is neither new nor uniquely Norwegian. Comparable patterns can be observed in Japanese minka, American summer cottages, and Mediterranean second homes, all of which illustrate how small-scale, rural retreats can become environmentally demanding traditions over time.

The core concern extends beyond emissions, land use, or architectural typology. It centres on how cultural norms surrounding leisure increasingly conflict with broader ecological commitments. Even in highly sustainable societies, everyday practices and recreational expectations can weaken the integrity of national environmental ideals.

Ultimately, the trajectory of Norway’s cabin culture shows how quickly recreational traditions can shift once comfort, accessibility, and expectations evolve. The challenge now is ensuring that these changes develop in line with the environmental standards Norway upholds elsewhere. Aligning cultural practices with national sustainability goals will determine whether the modern cabin remains a low-impact retreat or becomes another strain on an already pressured landscape.

A recent project by two students at the Bergen School of Architecture, Guro Skeie and Maren Stenersen, examines this shift directly. Their work, Hyttevett, addresses the growing mismatch between traditional ideals of simple cabin life and the increasingly resource-intensive reality. Drawing on their analysis, they outline a set of practical guidelines for cabin owners; measures intended to support more sustainable patterns of development and use.

Translation (provided by Google Translate):

Cabin rules

1. Avoid interference with valuable nature

2. Adapt the cabin to the terrain and conditions

3. Take into account the local environment and identity, use local resources

4. Be prepared for social and climatic changes, think "flexibility"

5. Respect the cabin, use it often

6. Make safe choices, do not disturb or destroy the ecosystem

7. Use your head, read the terrain

8. Turn around in time, there's no shame in scaling down

9. Save your energy, share ownership

Projects like Hyttevett, indicate a growing recognition of these tensions. Their proposals underscore that sustainability in cabin development cannot rely on technical solutions alone; it must also address the cultural habits and expectations that shape how cabins are built, maintained, and used.

As cabin culture continues to evolve, its future impact will depend on how effectively policy, design practice, and everyday behaviour can be brought into closer alignment. The challenge is not to preserve tradition unchanged, but to guide its development in ways that remain consistent with Norway’s broader environmental ambitions.

Comments